I

am almost certain that you have heard the man’s music, but probably never heard

his name. As I recall, the first time I ever heard one of his most popular

pieces was when I was seven years old, at a dance recital in which my cousin

Dianne was a participant. The melody stuck with me and since then I have often (and

fondly) listened to it, primarily as a band piece played by some municipal

band, such as the San Francisco Municipal Band at their Golden Gate Park summer

concerts. However now that I think about it, I hadn’t heard it for some years; yet,

the melody immediately popped into my head when I saw that the now Golden Gate Park

Band had announced its 2016 schedule. The melody was that of In a Persian Market and the composer was

Albert Ketelbey (August 9, 1875 – November 26, 1959)

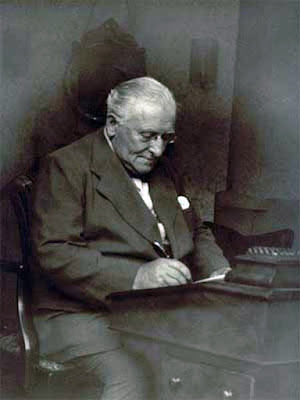

A

composer, conductor, and pianist, he was born in Birmingham, England and moved

to London in 1889 where he studied at the Trinity College of Music, and where

his abilities set him far apart from his classmates. After graduation however,

he surprised almost everyone by pursuing work not in classical music but as the

musical director of the Vaudeville Theater. Ultimately he gained fame as the

composer of some of England’s most favorite light music, what could have been

considered “pop tunes” of the day, and as a conductor of his own works.

He

also worked for many years for several music publishers such as the Columbia

Graphophone Company, as an arranger and orchestrator, and later wrote music for

silent films. While his pieces in the orthodox classical style of the day were

often widely appreciated, it was his light orchestral pieces that made him famous.

One of his earliest pieces, In a

Monastery Garden (1915) actually sold over a million copies and brought him

considerable notoriety. He followed this with In a Persian Market (1920), Cockney

Suite (1924), In the Mystic Land of

Egypt (1931), and In a Chinese Temple

Garden (1932) — best sellers all, both in print and on records, which made

him a millionaire. (See Below)

It

was during World War II that his popularity began to decline along with his

originality; indeed, much of his post-war works were actually reworked versions

of older pieces. Ultimately he retired, in 1949, to the Isle of Wight where he

remained until his passing.

In a Monastery Garden

In a Chinese Temple Garden

In the Mystic Land of Egypt